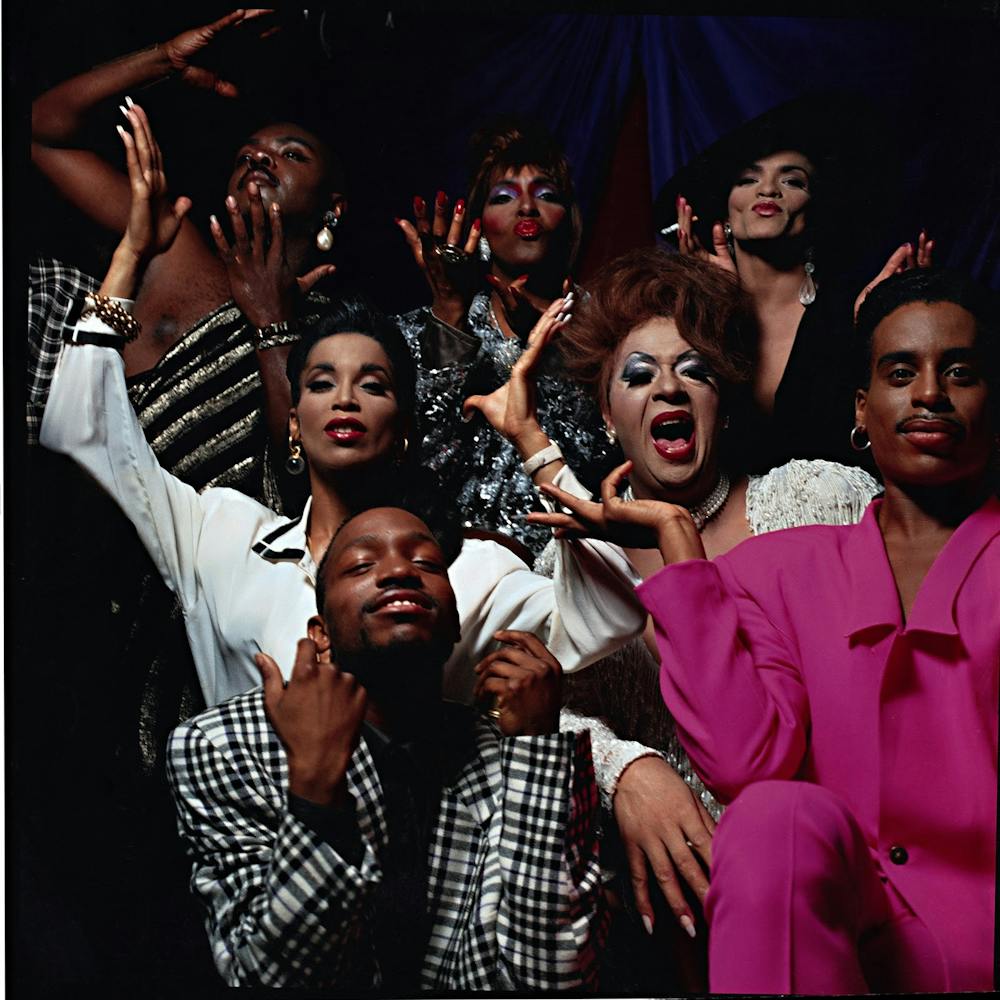

Watching “Paris Is Burning” today feels like watching a contemporary artifact, a paradox created by an old camera about people and culture that are distressingly recognizable. The grainy handheld camera of the late ‘80s that was used to film 70 hours of footage directed by Jennie Livingston, who’s a lesbian, harkens back to home movies and a style of underground film that doesn’t get much aesthetic attention anymore. The story of the queer drag queen and dance culture of New York City lets viewers see the contradictions of these nightly celebrations through the eyes of Black and Latinx queer, transgender, gay and lesbian people.

The film’s style and language can make the viewer think these stories were isolated to the ‘80s, a decade built on high fashion, and to New York City, a haven for subcultures. But rewatching “Paris Is Burning” while international protests for justice over George Floyd’s death extend into the beginning of Pride Month, it is clear that the scores of drag queen performers featured in the film can teach us more about today’s intersectionality, even from their ‘80s scene.

“Paris Is Burning” taught mainstream culture how to “vogue,” how to serve “realness” and, most importantly, about the realities of young genderqueer and gay Black and Latinx individuals.

Not every character in the film has their biological family to return to; some characters tell their stories about being kicked out of their homes when they came out to their families. Today, LGBTQ+ youth have a 120 percent higher chance of experiencing homelessness, according to a University of Chicago study.

But even without their given families, the Black and Latinx queer community of New York City still made “houses,” or organizations of young queer people who participate in drag balls and runways. Each house has a “mother,” an older, experienced drag queen mentor who shelters and trains new performers. New members usually adopt the house name as their own surname.

The House of LaBeija, featured in the film, has been welcoming youth since the '70s and is still performing. Created by Black drag queen Crystal LaBeija, you can see members of the house, like Pepper LaBeija, perform in the film.

“This is white America,” Pepper LaBeija says in the film when discussing the struggles Black drag queens face in mainstream society. “And when it comes to the minorities; especially Black — we as a people, for the past 400 years — is the greatest example of behavior modification in the history of civilization. We have had everything taken away from us, and yet we have all learned how to survive. That is why, in the ballroom circuit, it is so obvious that if you have captured the great white way of living, or looking, or dressing, or speaking — you is a marvel.”

Watching the film today, LaBeija’s quote stands out because it echoes the conversation America has been submerged in, following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Tony McDade, a Black trans man, at the hands of police officers.

Their deaths have brought protesters and Black leaders around the country to the streets against the systemic struggles they have faced in law enforcement and government for the past 400 years. “Paris Is Burning” shows that these conversations were happening in the ‘80s, but especially in the spaces occupied by persecuted Black queer individuals.

LaBeija’s quote also calls forward the contradictory nature of “realness” in drag competitions. “Realness” is the performer’s ability to pass off as something that they are not, “to be able to blend,” the film explains. Competition categories, like “executive realness” and “looking like the boy who robbed you a few minutes before coming to Paris’ ball,” test whether performers can assimilate into the category with fine accessories that they maybe attained through, as the film explains, theft or prostitution.

“The idea of realness is to look as much as possible as your straight counterpart,” queen Octavia St. Laurent says. “You look like a real woman, or you look like a real man, the straight man … It’s really a case of going back into the closet … Rather than have to go through prejudices about your life and your lifestyle, you can walk around comfortable, blending in with everyone else.”

While the ball circuit and the film celebrates being able to show “realness” when performers win tall gilded trophies, it still notes the contradiction of asking queer people to hide their identities for recognition. The idea of assimilation, of being able to become the figure you may never fully be able to be because systemic homophobia and racism requires you to discard a valuable identity, is true performance.

Over thirty years later, LGBTQ+ people are still “performing realness” in their daily lives. Twenty-nine states do not fully protect LGBTQ+ people against discrimination on either sexual identity, gender identity, or at all in public and private sectors.

After the extravagant dancing, creative costuming, exaggerated makeup, the juxtaposition of small, crammed New York City apartments and the hard nightlives of queer and gay men trying to survive, the film takes an even harsher look at reality of not only life, but death.

Venus Xtravaganza, a young and recurring performer, was murdered. The film theorizes that one of Venus’ wealthy companions discovered she was transgender and killed her. “But that’s part of being transsexual in New York, that’s surviving,” Angie Xtravaganza, Venus’ house mother, says in the film.

When a transgender man, Tony McDade, was killed in an police officer-involved shooting on May 27, Gina Duncan, the director of Transgender Equality for Equality Florida told Mother Jones, “Talking about Tony’s earlier brushes with the law should not diminish the humanity of this being a person who is now dead and certainly shouldn’t diminish the fact that society failed Tony.”

It’s depressing to know about Venus’ murder and wonder how society in the ‘80s failed her.

The overlap of Black Lives Matter protests and Pride this year hightlights the enhanced persecution of Black queer people and the importance of intersectionality in both movements.

“Paris Is Burning” shows that these two moments have been and still are inextricable. The queer community featured in the film cannot talk about their experience as gay or transgender people without also talking about the effect their racial identity has on their sexual and gender expression.

For non-Black or non-queer people, watching this film can be a starting point for understanding the world of these identities, the language that is used to start communities and the daily individual and long-term systemic hardships Black, Latinx and queer people face due to unchangeable identities. The decades-old film is as contemporary as films that feature these communities now, like “Port Authority” released in 2019.

“Paris Is Burning” made “vogue” dancing mainstream, but it can also help make mainstream the ideas of acceptance and anti-discriminatory policy. The film shows that there is still more to be done, there is still more to learn. So in the great tradition of “Paris Is Burning,” start reading.