The following piece is an opinion and does not reflect the views of The Eagle and its staff. All opinions are edited for grammar, style and argument structure and fact-checked, but the opinions are the writer’s own.

The Oxford Languages dictionary defines kawaii as an adjective or noun in Japanese popular culture that means to appeal endearingly or have the quality of being cute.

I disagree.

My definition of kawaii is an adjective describing an object, human, event or practically anything as cute, pure, innocent, infantile and endearing, with an emphasis on a youthful appeal.

As a Japanese American, my definition reflects experiences with kawaii’s usage linked to Japan’s obsession with small or childlike things, while Google defines it as a synonym for cute.

With kawaii culture’s normalization in Japan, people are unaware of how pedophilia, sexism and patriarchal ideals have seeped into everyday life and the world’s recent glamorization of Japan doesn’t help.

It’s time to critique Japan where it needs it.

Kawaii culture, as we know it, originated primarily in the 1970s as consumer subcultures grew amid the booming economy.

During this era, cuteness was established through childish handwriting, speech, dress, products and cafes. Specifically, the idea of childlike women emerged to portray innocence and reduce women into something to be taken care of — a sexist, patriarchal idea that continues today.

In the rampant consumerism of the 1980s, characters well known today, like Hello Kitty, emerged, uplifting kawaii culture.

Such commercial powers of the kawaii aesthetic convey a sense of helplessness and neediness that appeals to a consumer’s vulnerabilities to purchase these products.

Viewing kawaii through a historical lens, it seems like Japan evolved past the initial reason kawaii gained popularity in the first place, of portraying the innocence and helplessness of women, and moved on to the creation of cute characters.

In reality, the historical undertone of the word is more subtly communicated today through beauty standards, everyday compliments and comments reinforced on social media, making it dangerous. When an aesthetic becomes so normalized, necessary critiques will be dismissed and incorrect traditional standards will never change.

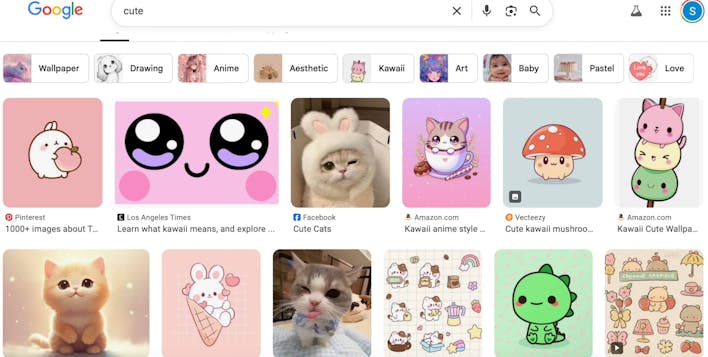

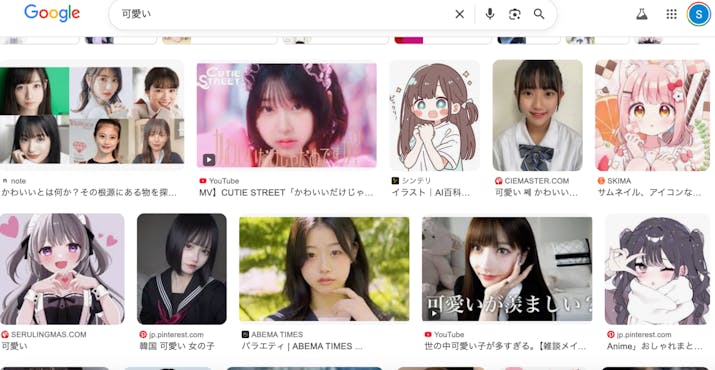

A 2017 University of California, Los Angeles study provided a concrete example of how kawaii goes beyond the word “cute” and is permanently integrated into Japanese culture by comparing images from Google searches for “cute” and “kawaii.”

I also conducted this experiment in 2025 and had the same results. Searching for “cute” in English displays small animals, cartoons and pastel characters, while searching for “可愛い” (kawaii) in Japanese shows sexualized pictures of women.

These results reflect Japan’s idolization and requirement of Japanese femininity’s association with kawaii, and experts like Asano Chizuko said it reinforces the stereotype of women being “fragile, incompetent and unable to take initiative.”

While the stereotypes are a problem, a deeper issue lies in how Japan’s obsession with kawaii promotes innocent and childlike qualities, raising questions about when that obsession borders on pedophilia.

Kawaii is a standard women strive for in Japan, and it shows up subtly in popular photo booth filters that emphasize childlike features, downward eyeliner for innocent eyes or a recent trend of adults buying bags catered to children for themselves.

In the United States, viral social media content and influencers like Hannah Kae — who posted and later apologized for childlike photos and videos — have been called cringey or have received extreme backlash for promoting such behavior. But in Japan, this content is normalized with kawaii praises flooding comment sections.

When isolated, these instances seem innocent enough, but countless examples from everyday life build up, making the issue more meaningful and in need of scrutiny.

This culture of kawaii has been normalized without raising concern because of Japan’s history of a lack of sexual abuse protections for children.

Child pornography only became illegal in Japan in 2014, and the country raised the age of consent from 13 to 16 only recently, in 2023. It is noteworthy to mention that the child pornography ban does not apply to manga or anime — Japan’s leading inventions.

With this evidence in mind, even slightly questionable usage of kawaii leads me to connect it to the broader theme of pedophilia and sexualization of children.

Japan is nowhere near solving this issue, and the glamorization of Japan by America and other countries is contributing to this narrative.

Although there is beauty in Americans appreciating and uplifting Japanese culture, it is necessary to critique some wrongs without being overpowered by the obsession with the country.

Especially as these issues are normalized in Japan, change will not occur until those outside of the country begin to point it out.

As a Japanese American who proudly cherishes the beauties of Japanese culture, I am embarrassed and horrified by the sexual undertone in Japan’s kawaii culture and people in Japan should be too.

As people living in America who can recognize these faults, it is crucial for us to write and talk about these issues, so that media outlets here and in Japan will pick them up. For direct impact, people can respectfully call out problematic content on digital platforms and provide outside insight to creators in Japan. To contribute indirectly, don’t engage with the content at all, unless providing critiques, to dissuade creators from uploading them.

Though critiquing and commenting can increase engagement with certain videos or photos, it may be unavoidable to give the content an initial spotlight to open the controversial conversation to more people.

When such harmful customs are deeply ingrained in a country, people living there become desensitized and need to be held accountable by another country with differing perspectives. As Japan’s popularity is booming, now is the time to praise and uphold what’s beautiful about its traditions while also helping the country recognize what needs to be left behind.

Sara Shibata is a senior in the School of Public Affairs and the School of Communication and a columnist for The Eagle.

This piece was edited by Quinn Volpe, Alana Parker, Addie DiPaolo and Walker Whalen. Copy editing done by Avery Grossman, Arin Burrell, Paige Caron and Nicole Kariuki. Fact Checking done by Andrew Kummeth.