The National Museum of Asian Art recently started a “Monthly Matinee” event to screen several iconic Japanese films. On the second Wednesday of every month in the Meyer Auditorium, the museum screens a piece of Japanese cinema. The next film is going to be Ishirô Honda’s “Mothra vs. Godzilla” (1964) on March 13.

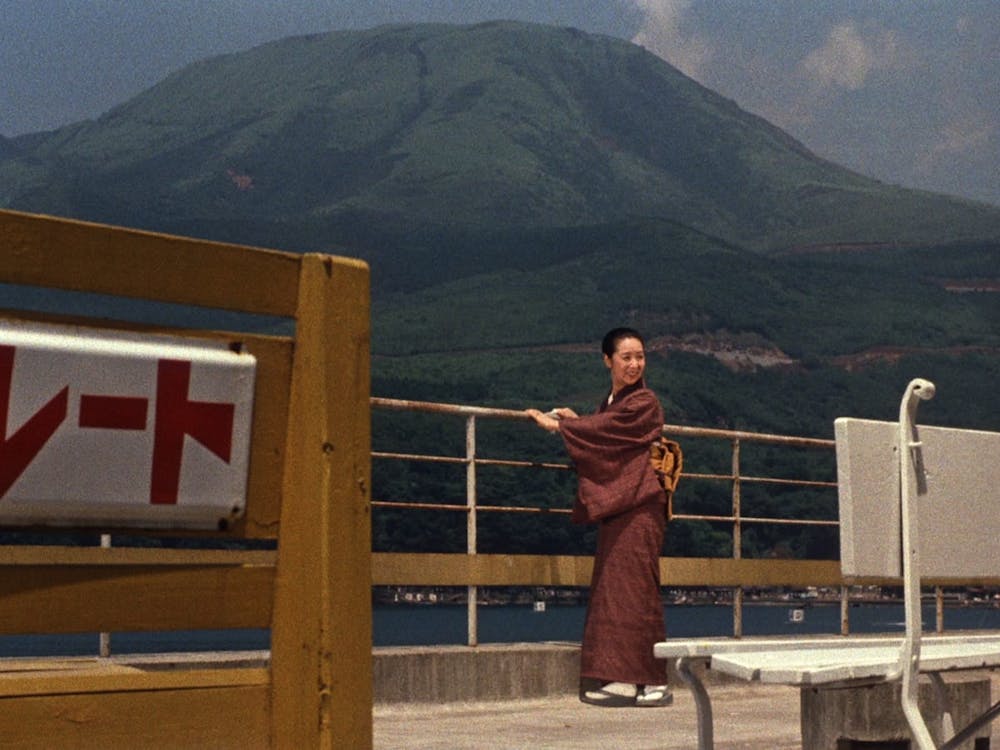

On Feb. 14, the museum showed Yasujirō Ozu’s 1958 film “Equinox Flower.” A charming film from the iconic director, “Equinox Flower” was a lovely viewing this Valentine’s Day.

Director Ozu is one of Japan’s finest filmmakers. Influential, iconic and innovative, Ozu made movies tackling marriage, family and the generational divides in post-war Japan.

Ozu grew to cinematic stardom through his unique style of filmmaking. His camera remained still and low to the ground, as he strove to create an honest, humanistic depiction of his stories.

Ozu’s “Equinox Flower” depicts the struggles between Japan’s traditional, conservative values and rapid modernization. Ozu tells the story of businessman Wataru Hirayama’s (Shin Saburi) disapproval of his eldest daughter Setsuko’s (Ineko Arima) unarranged marriage to a young man named Masahiko Taniguchi (Keiji Sada).

“Equinox Flower” (1958) does not stray far from Ozu’s typical work, but it was the director’s first experimentation in color — although you’d never guess it. The use of color and visual storytelling in “Equinox Flower” are some of its most compelling qualities.

The film’s palette features many muted blues, grays and greens that create a drabness about its world.

Amidst this dry, traditionalist background lives a bright, everlasting love, represented by the eye-catching traces of bright, bold reds in the film. Sonically matched by the film’s swooning score, “Equinox Flower” has a consistently romantic tone that seeps through the film.

The film’s music and visuals demonstrate an underlying tension between Japan’s conservative values and the younger generation’s more liberal views. “Equinox Flower” also manages to display the gulf that separates them, with the framing often creating literal gaps and spaces between younger and older characters.

The stiff movement and language of Hirayama are in stark contrast to the emotive and more hopeful tendencies of the younger characters.

A constant struggle of reluctance versus eagerness manifests in this film. Hirayama rarely smiles and remains unbothered by the prospect of his daughter’s marriage. On the other hand, both of Hirayama’s daughters relish in the excitement of the wedding and married life.

Although “Equinox Flower” is a satisfying and relaxing watch, it never reaches exceptional depth and lacks some substance. The film suffers from just how “slice of life” it is.

The film throws us into characters’ lives and the thick of the plot without any sufficient emotional investment being built. The plot and characters feel slightly underdeveloped because of this.

Real emotional connections are hard to come by in this film, leaving “Equinox Flower” to ultimately pale in comparison to the affectivity of an earlier Ozu film: “Tokyo Story” (1953).

However, Ozu still showcases his immense talent with “Equinox Flower,” capturing this simple story with honest and distinguished filmmaking. The film is like a gentle poem, weaving a soothing yarn about family, love and marriage.

If you’re looking for some calming, elegant and artistic cinema, “Equinox Flower” is worth a watch.

This article was edited by Bailey Hobbs, Zoe Bell, Sara Winick and Abigail Pritchard. Copy editing done by Luna Jinks, Sydney Kornmeyer and Charlie Mennuti.