From: Silver Screen

REVIEW: ‘Titane’ is mechanical horror with a heart

Sex, serial murder, surprise pregnancy and a very special car: right from the opening, “Titane” is a lot to take in.

The award-winning shocker premiered at the Cannes Film Festival where it won the Palme d’Or before moving on to win the People’s Choice Award for Midnight Madness at the Toronto International Film Festival, and being released for its theatrical run. The brainchild of writer-director Julia Ducournau, “Titane” is not her first foray into body horror or controversy. Ducournau’s 2016 film, “Raw,” generated similar discourse due to its graphic violence. In what is becoming somewhat of a directorial trademark, her new film is not for the faint of stomach.

Beginning with a death and ending with a birth, “Titane” has been characterized as a body horror film, but truthfully, it’s much more complicated than that. While there are moments that will undeniably make you squirm, the vast majority of the movie is much more tender. By presenting feminine and masculine icons through a stripper and a fireman, then slowly undermining the audience's gendered expectations of them, Ducournau relishes in forcing the audience to accept that the main characters are neither conventionally feminine nor masculine.

One of those main characters is Alexia (Agathe Rousselle). Tall, blonde and tattooed, she works as a dancer in a car show. She is immediately identifiable by the titular titanium plate in her head, the product of a car crash in her childhood. After following her through her routine and watching her navigate an uncomfortable bind with another dancer in the showers, we see a male patron follow her car as she leaves work. This is, regrettably, a horror story that far too many women are familiar with. The trope, however, is flipped on its head when Alexia charms and disarms the man, then kisses him and uses that opportunity to stab him to death.

Alexia continues on her killing spree by violently murdering several people at a house party, including another dancer from the club. After this outburst, we are treated to a sequence where Alexia begins to comprehend the gravity of her situation. With the help of a would-be victim, the police have begun circulating a sketch of Alexia as a suspect. To evade capture, she shaves her head, binds her chest, breaks her nose and turns herself in claiming to be Adrien, a boy who has been missing for ten years.

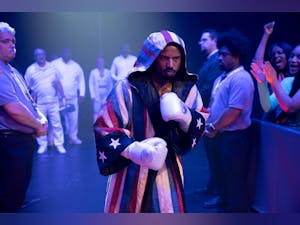

Adrien’s father is Vincent (Vincent Lindon), who is by all accounts a crumbling icon of masculinity. This aging fireman also grapples painfully with the gendered expectations society has for him, both as a father and in his occupation as captain in the firehouse. While his turmoil is not as outwardly violent as Alexia’s, it is still a source of pain and we are eventually shown that his identity is just as complex as Alexia’s.

Nowhere is the fluidity of Vincent and Alexia’s identities made more apparent than in a scene that occurs at roughly the midpoint of the film. Alexia is sitting at the dinner table eating with Vincent, who is trying to get her to engage in conversation. She is still unable to speak, lest she reveal her true identity.

After multiple attempts to engage her in conversation by wearing her down, Alexia gets up to leave the table while Vincent tries a new strategy to open her up: dance. He puts on “She’s Not There” by The Zombies and starts dancing. It’s a moment that in a different light would seem almost comic — the macho fireman happily dancing to a flower-power era pop song. But in a scene like this, it comes across as an entirely heartfelt and genuine moment of vulnerability. This is Vincent lowering his guard in the hopes that Alexia (or Adrien) will follow suit.

Initially she does — she comes back towards him and they begin dancing hand in hand. But during the short, two-minute duration of the song their dance gradually becomes more aggressive and eventually becomes a full-on fight. In under two minutes, the characters swing from a moment of peace and vulnerability back to their assumed hostile postures. The emotional change is most noticeable in Vincent, who seems to revel in his small reprieve from maintaining the uber masculine image he so desperately clings to.

It is that depth of emotional complexity that makes “Titane” such a fascinating film, and what gives it such an ironclad grip on your mind for weeks after viewing it. Films that try to ask tough questions of their audience come a dime a dozen today; instead, “Titane” asks you to probe deeper and question your own identity.

“Titane” was released in theaters on Oct. 1.