“One of our Old alumnia Mrs Daniela is downsizing and looking to give away her late husband’s piano to a loving home,” the email began.

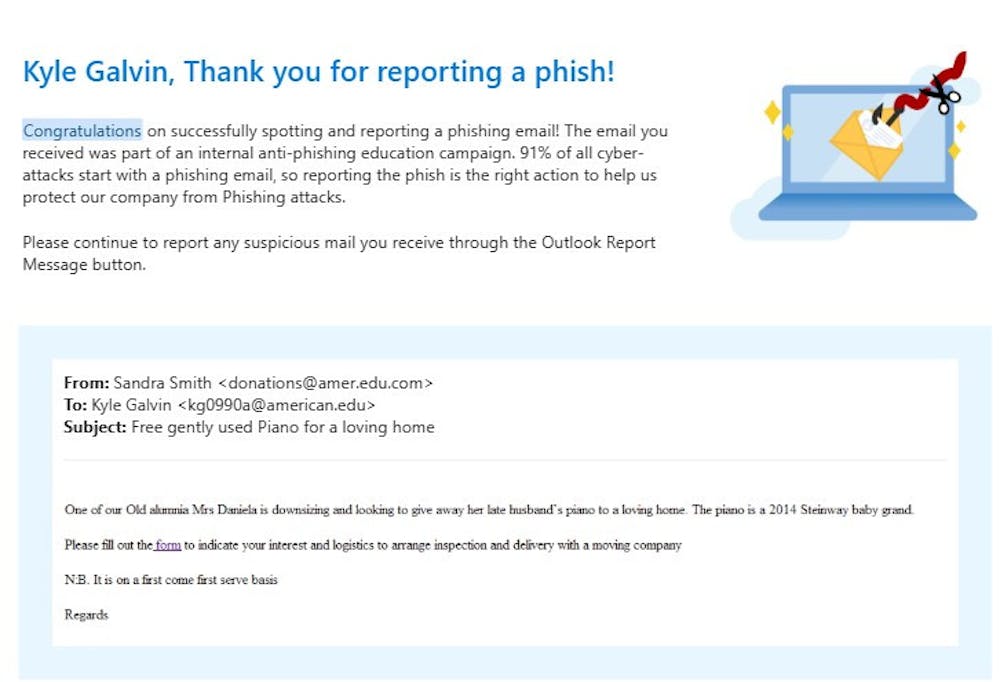

While claiming to be from a Sandra Smith, the Oct. 30 email from “donations@amer.edu.com” was actually part of an American University internal anti-phishing education campaign.

A number of these emails appeared in student Outlook inboxes in October, which is National Cybersecurity Awareness Month, posing as everything from PayPal to University President Jonathan Alger.

The University is one of many institutions that use Microsoft Attack Simulation Training tools to send students fake phishes throughout the month, said Regina Curran, the University’s director of privacy and cyber policy.

“From an information security standpoint, phishing attacks can be particularly fruitful with a college audience,” Curran said.

Students who recognized and reported the phishes were sent follow-up thank-you emails. But if students failed to recognize the phish and followed the email instructions, they were brought to a phishing training page on the University website.

Curran said phishes work on college students for two reasons. First, she said cyberattacks can be more effective when they relate to the context of a person’s life, and college is where many students interact with their email more for career advancement — making fake job scams tempting.

Second, many students view their University inbox both quickly and on their phone — which Curran said can make falling for a phish a split-second decision. She said sometimes a student’s email address could pretend to be the University, saying ‘we're going to shut off your access to your account.’

“Knowing that that’s coming from a student email, as opposed to a staff email, should be a dead giveaway,” Curran said. “But if you can’t see that full email address because you’re looking at it on a mobile device, maybe it’s a little bit easier to kind of fall for it.”

The set of phish emails claiming to be from Alger sent to a student’s iCloud.com inbox, and obtained by The Eagle, had grammar mistakes, missing signatures and email addresses outside of the University system.

One email, which began with “EMERGENCY,” requested assistance with an “urgent task” Alger needed help reviewing. While the subject line displayed the president’s name, the email was sent from “companyworkmail86@gmail.com.”

“I have a brief errand that needs your help. For convenient coordination, could you kindly provide your current personal phone number?” read the other email, from “managementmail878@gmail.com.”

As an anti-phishing measure, the vast majority of american.edu email addresses are only able to send out emails to 500 recipients, according to Curran, who said other hypothetical institutions where scammers could send out thousands of emails make for more enticing targets than AU. Alger is one of a handful of University email accounts whitelisted to contact more than 500 others, however.

Curran and AU’s Director of Technology and Analytics Andrew El-Kadi held a data privacy workshop for students on Sept. 24. In addition to subjects like encryption and social media privacy, they also discussed how most hacking happens through social engineering, the use of psychological influence of people into performing actions or divulging confidential information — especially phishing.

“It preys on feelings and emotions, things like fear, things like urgency,” El-Kadi said at the workshop. “You know, your boss is texting you, and you have to send this money via whatever [app] very quickly.”

El-Kadi likened social engineering to walking into a campus space in business attire, where you’re then able to command respect without ever having to identify yourself. He said that applies to digital access as well.

“I can say, ‘Hey, can I see your phone?’ And the person will hand it to me, just based on them being a student and my age, for example, right?” El-Kadi said hypothetically. “They’re like, ‘Oh, you must be an administrator here,’ And they hand it to me, and I now have access to some of these devices.”

Recognizing which emails are from University accounts is one key way to identify phish attempts, Curran told The Eagle. A lot of the University’s stock emails, for example, are sent using Emma, a Nashville-based email marketing and automation platform. Emma’s brand name can be found at the bottom of an email along with managing and opt-out preferences, Curran said.

As for the Alger emails requesting your phone number, the answer is all in the address, according to Curran. She said there are never emails from the President from anything other than president@american.edu.

“What they’ll do is they’ll try to mimic the front end, because that’s a little easier than the, you know, at@american.edu right?” Curran said. “So they might say ‘president@’, and then it's something that isn’t exactly ‘american.edu,’ right? Because then it’s not in the system.”

Which means ‘donations@amer.edu.com’, Sandra Smith or Mrs. Danelia’s piano aren’t in the system either.

This article was edited by Owen Auston-Babcock, Abigail Hatting and Walker Whalen. Copy editing done by Sabine Kanter-Huchting, Avery Grossman and Ava Stuzin.