From: Silver Screen

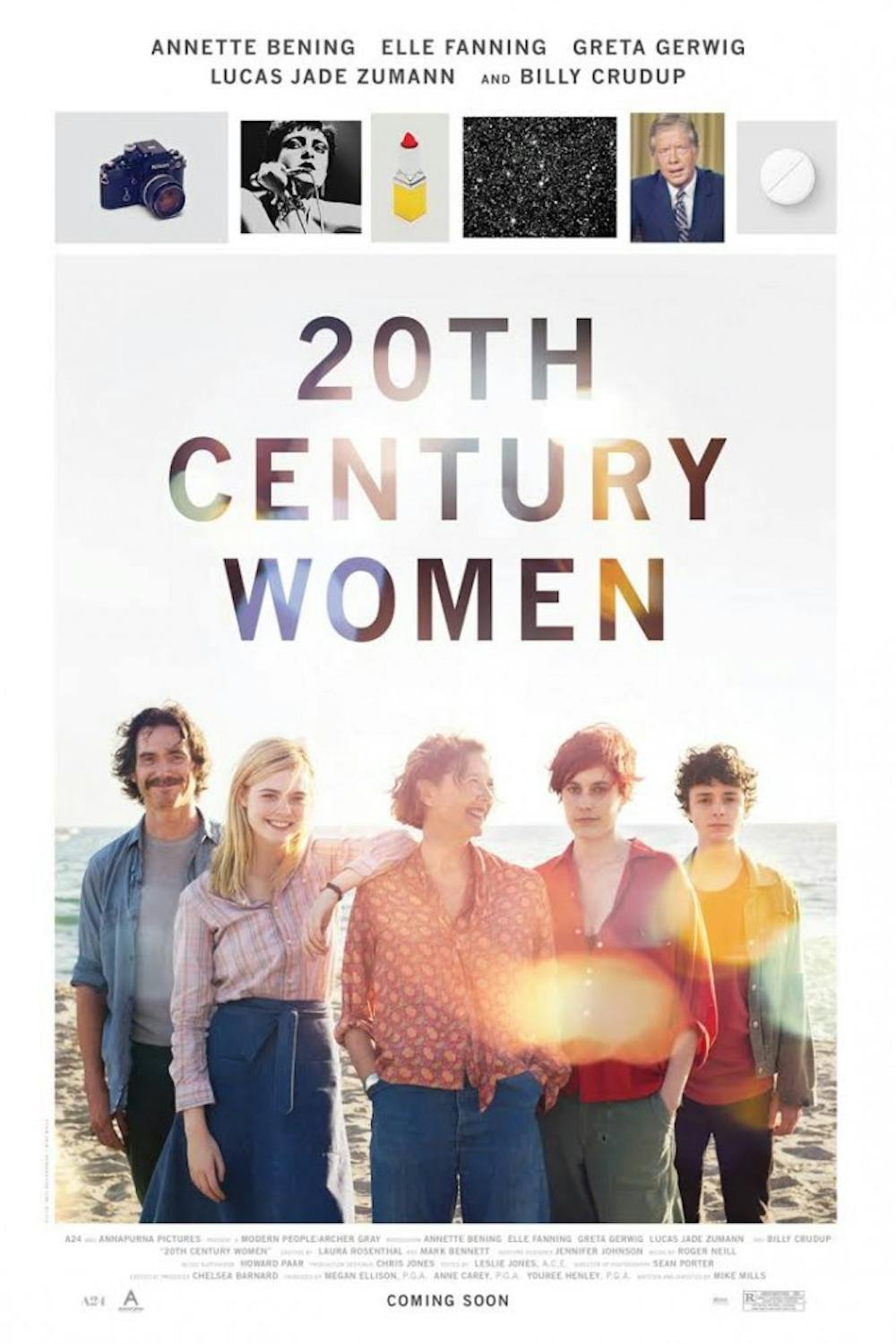

20th Century Women provides aching look at what it means to grow up in a changing world

In 1979, it was no easier to be a young person than it is now. Using the landscape of changing politics, rock bands and a cynicism with the world, director Mike Mills’ 20th Century Women reflects on the internal conflict that comes with growth.

The film follows 55-year-old single mother Dorothea (Annette Bening) and her 15-year-old son Jamie, played by newcomer Lucas Jade Zumann, as they both attempt to find happiness and meaning in the complex world of Santa Barbara, California. Feeling distant from her son and hoping to raise him well despite the absence of a father figure, Dorothea enlists the help of her tenant, Abbie (Greta Gerwig), and Jamie’s ‘more than a friend,’ Julie (Elle Fanning). Together, three women of three different generations try to give direction to Jamie while searching for it themselves.

As the title suggests, this film is less about Jamie and more about the experience of womanhood as seen through his eyes. Bening is luminous in her portrayal of Dorothea. A woman born several generations behind those with whom she interacts, she listens to “As Time Goes By” from Casablanca and chain smokes cigarettes even though she knows the health risks. There is a stubbornness in her inability to change, yet there is a strength there too. Toward the latter part of the film, Dorothea and her other tenant, William (Billy Crudup), dance together. Playing Jamie’s favorite band, Talking Heads, in order to try to understand him, it is a sublime moment. Although they begin to move to the song in a bit of a stilted fashion, the synchronicity to their movements allows them to let go of their awkwardness and then there is nothing but pure joy.

Nevertheless, joy is often hard to come by due to the isolation of being a women in American society, and director Mills does not shy away from showing it. Motherhood, something Abbie deeply wants to experience, is not accessible to her. Portraying a survivor of cervical cancer, Gerwig gives Abbie a sensitive vulnerability masked by a personality as bright and fierce as her red hair. Although she is full of energy and life, she is also deeply afraid of the future because hers is bogged down by the past. In one scene, Abbie asks William to role play with her so she does not have to be in her own skin while she is having sex with him. There is such a tenderness to the moment when he gently touches her and says, “I’m sorry.” You can tell that he means it.

While Abbie struggles with intimacy, the tall and beautiful Julie does not have to feign openness when it comes to sex. Disconnected from her family and community, she finds solace in sleeping with boys, even though she admits she doesn’t like it half the time. However, it’s “the other half of the time” that keeps her from stopping. Fanning becomes Julie, embracing the toughness the character wears as a shield and letting the scared young girl hiding beneath slip through the cracks every so often. Jamie’s unwavering affection and love for her is unsurprising. It is built around her aura of mysteriousness. Constantly sneaking into his bed, staying there at night and slipping away in the morning, she is a beguiling and confusing presence in his life as he tries his best to be a “good man.”

Like his previous film Beginners, 20th Century Women is semi-autobiographical and Mills’ filmmaking feels like a memory. His intimate, gauzy shots are revisionist, remembering his past in both romanticized fragments and cohesive pieces. In many ways, it reminds me of how I remember my own past and the conflicting feelings of disappointment and elation, loneliness and connection that come with family, love and relationships. By translating memory into art, Mills brings a new power to the voices he has heard. While critics and skeptics may complain that film is sentimental, its sincerity and its wit give it emotional depth from start to finish.

Grade: B+

Naomi Zeigler is a senior in the College of Arts and Sciences and is the Opinion Editor for The Eagle.

silverscreen@theeagleonline.com