At the top of the stairs at the Phillips Collection art gallery, attendees must make an initial choice between two exhibitions to explore, but not between two stories. On view from Oct. 8 to Jan. 8 of next year, Jacob Lawrence’s “Migration Series” and Whitfield Lovell’s “Kin Series and Related Works” each take the audience on trips back to the lives of African-Americans during the pre-World War II era.

Lawrence , the premier painter of the Harlem Renaissance, sought support in 1940 for a monumental project: a 60-panel series of paintings depicting the Great Migration of African-Americans from the agricultural south to the labor-deficient north that began in World War I, as noted on the Phillips Collection website. The museum presents its odd-numbered panels reunited with the Museum of Modern Art’s even numbers for the complete experience of the series.

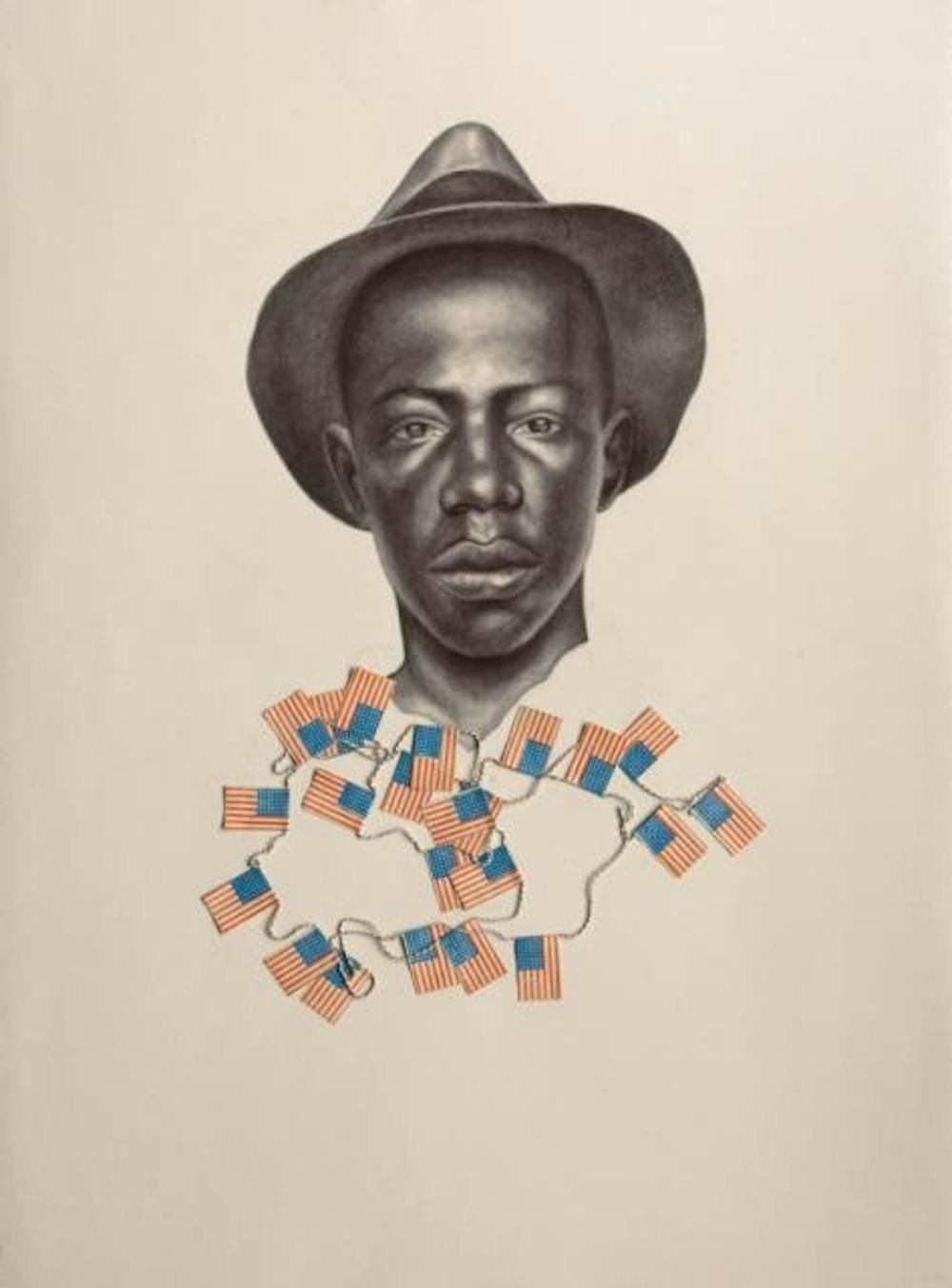

Beginning in 2008, “Kin Series and Related Works” also features a numbered series, in this case consisting of Lovell’s soft-yet-photorealistic charcoal portraits paired with mementos ranging from gilded hand mirrors to ankle chains. The two exhibitions have distinctly different artistic styles, but complement and build off of each other in a way that gives a unique look into a less popularized era of Black American history and culture.

The first portrait of the Kin Series, “Kin I,” is one of the first pieces in the exhibition and sets up the framework for the rest of the series. It is a nearly life-size charcoal portrait on cream-colored paper of a young Black man in an old-fashioned hat, with a string of miniature American flags affixed below it. The faces in the Kin Series are all real, based on vintage photographs collected by Lovell, and when combined with his mastery of charcoal, they feel alive. Lovell combines the portraits with ephemera, but not unless he feels like the object and the portrait are a perfect match. In addition to the Kin Series, there are life-size, full-body portraits on antique wood, and even works that incorporate audio.

While Lovell’s pieces more intimately tell the story of individual African-Americans, the Migration Series tells the story of a people. The 60 equally-sized panels were created methodically, carefully planned and then all painted with tempera simultaneously by color from light to dark to ensure consistency. The sense of exertion and aspiration conveyed by the series is reinforced by its self-imposed parameters: a small palette of colors, stark diagonals, and the absence of detail in most faces.

The two series share a parallel structure as well as a parallel story, but their opposite narrative scopes merge beautifully, the featureless faces of Lawrence’s series each having a counterpart in Lovell’s. Many of the accompanying objects in the Kin portraits -- kitchenware, brambles, chains -- are symbols that reappear in the Migration Series. The Phillips Collection has on view two exhibitions, but together brings one experience more powerful than either on its own. It’s an infrequent chance to see the entirety of The Migration Series, and perhaps a once-in-a-lifetime chance to see two series of art so intimately in conversation with each other.

Admission to the Phillips Collection is $12, but flash your American University ID to get in at a discounted $10.